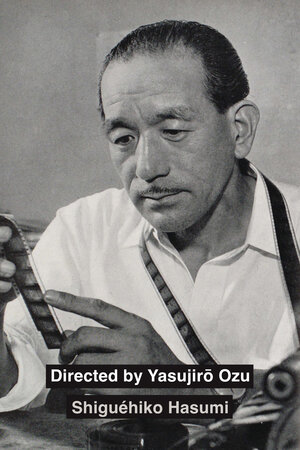

Stephen Sarrazin présente dans DC Mini, nom emprunté à Kon Satoshi, une chronique pour aborder « ce dont le Japon rêve encore, et peut-être plus encore ce dont il ne rêve plus ». Il nous livre aujourd’hui ses réflexions sur la traduction par Ryan Cook de l’ouvrage Directed by Yasujiro Ozu de Hasumi Shigéhiko.

(English version bellow)

Directed by Yasujiro Ozu, Hasumi Shigéhiko

Traduction de Ryan Cook avec une introduction de Aaron Gerow

University of California Press, 2024.

Automne Tardif

A la mémoire de David Bordwell

Vingt cinq années ont passé depuis la traduction française de ce même ouvrage par Réné de Cecatty, Nakamura Ryoji, avec la participation de Hasumi Shigéhiko, parue dans la collection Auteurs aux éditions des Cahiers du Cinéma. L’ouvrage paraissait dans sa version originale au Japon en 1983.

Hasumi mena une carrière exceptionnelle à Tokyo, d’une ampleur telle qu’il soit peu probable que l’événement se reproduise. Professeur respecté et admiré à l’université Rikkyo, francophile et francophone, critique et théoricien ayant introduit, tout comme son jeune contemporain de l’époque, Asada Akira, les œuvres de Roland Barthes, Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, et Jacques Derrida, il sera également invité à concevoir des programmations de cinéastes de genre, tels Suzuki Seijun et Tai Kato, dans d’importants festivals internationaux. Enfin, il deviendra président de la prestigieuse Université de Tokyo. La revue de Serge Daney, Trafic, publia quelques uns de ses essais, notamment sur John Ford ; parmi ses admirateurs en France, on retrouve Jean-Michel Frodon, autrefois directeur des Cahiers et critique pour Le Monde, et le traducteur et spécialiste de l’œuvre de Yoshida Kiju, Mathieu Capel.

Mais à l’heure où la réflexion en France sur Ozu Yasujiro prend la forme d’un beau livre de Pascal Alex Vincent (1), la méthode Hasumi, inévitablement citée, aura attiré un nombre restreint de chercheurs universitaires. Quant à la perception de l’œuvre de Ozu au sein de la cinéphilie en France, avançons qu’elle a pris le pas sur celles de ses pairs.

La scène universitaire anglo-saxonne est toute autre, et le nombre d’enseignants, de doctorants se penchant sur Hasumi surprend par son enthousiasme et par la proximité des membres de cette communauté. A cet égard, le travail accompli par Ryan Cook devrait lui assurer leurs louanges. Mais pour celles et ceux qui comptent découvrir le regard de Hasumi sur Ozu, ou le redécouvrir, cette traduction est désormais un magistral outil de référence. Cook, lui-même professeur de cinéma ayant pris une pause pour se consacrer à cette tâche, maîtrise la langue et l’écriture japonaises, et, dans son introduction, insiste sur celle-ci et sur sa volonté de souligner ce qu’en fit Hasumi, rappelant l’effet Barthes d’un degré zéro, mais aussi les études littéraires de l’auteur et l’influence probable de Flaubert sur son écriture.

Ryan Cook nous annonce par ailleurs son acharnement à traduire le style de Hasumi, évoquant le titre exact de l’ouvrage, signifiant ‘directed by Yasujiro Ozu’, et rêvant sa traduction ‘directed by Shiguéhiko Hasumi’. Hasumi était pourtant de la version française, accompagné de deux importants traducteurs de littérature japonaise, et en cela les deux versions s’éloignent l’une de l’autre. Le lecteur de cette nouvelle traduction hantera davantage les sphères du monde universitaire.

Bien que Aaron Gerow se tourne au début de son texte vers une revue de cinéma anglaise, Sight & Sound, et les places qu’occupent Voyage à Tokyo et Printemps tardif dans leur palmarès des cent meilleurs films de l’histoire du cinéma, il soulève avec justesse des points importants, notamment le pouvoir qu’exerça Hasumi sur une génération d’étudiants qui deviendront critiques et cinéastes (2), se retrouvant autour de l’édition japonaise des Cahiers du Cinéma. Encore aujourd’hui, Hamaguchi Ryusuke (adaptateur de Murakami Haruki) insiste que ce livre fut le plus important de sa vie (appelant ainsi à la prudence du lecteur…). Mais aussi qu’il existe désormais de nouveaux chercheurs internationaux qui peuvent lire les textes dans la langue, et contribuer à des essais en japonais, à la manière de chercheuses qui firent le trajet inverse telle Kinoshita Chika. Ce point touche à l’une des critiques opérantes chez Hasumi, ce dernier ne trouvant grâce ni dans le livre de Paul Schrader, ni celui de David Bordwell, et tous les autres qui persisteraient à faire de Ozu un cinéaste du moins alors que ce qui est ozuesque pour Hasumi tient de l’abondance. On retrouve ainsi les chapitres dressant la liste des actions, des états, des mets, que mènent, traversent, et préparent les personnages, avant d’atteindre l’émotion. Gerow précise que Hasumi est moins préoccupée par une célébration auteuriste de Ozu mais plutôt par une occasion de critiquer la notion même d’auteur, au point de ‘sacrifier cette unité auteuriste’ (3). En 1983, la notion d’auteur était une denrée fragile au sein de la pensée française…

Pour celles et ceux d’entre nous qui ne lisent pas les kanjis, ou qui peinent à se frayer un chemin à travers les phrases de Hasumi, dont la longueur rivalise avec Proust ou Henry James, cette version méticuleuse et précise, en contact direct avec le texte, avec un côté, un supplément maverick, fera date.

Stephen Sarrazin.

1- Le même éditeur, Carlotta, aura d’autre part publié les carnets d’Ozu.

2- Parmi ceux-ci, citons Aoyama Shinji, Shinozaki Makoto, et en périphérie, Kurosawa Kiyoshi. Rappelons également qu’en 1999, un an après la sortie de la publication française de son Ozu, Hasumi s’entretenait avec Kitano Takeshi pour l’épisode de Cinéma de notre Temps, qui lui était consacré.

3- Aaron Gerow, Shigehiko Hasumi and Viewing Films Studies Anew, in Directed by Yasujiro Ozu.

ENGLISH VERSION

Directed by Yasujiro Ozu, Shiguéhiko Hasumi

translation by Ryan Cook with an introduction by Aaron Gerow

University of California Press, 2024

Late Autumn

Twenty-five years have passed since the French translation of this same work, by Réné de Cecatty, Nakamura Ryoji and Hasumi Shiguéhiko, appeared in the Auteurs collection published by Cahiers du Cinéma. The original version was published in Japan in 1983.

Hasumi had an exceptional career in Tokyo, the measure of which is unlikely to be repeated. A respected and admired professor at Rikkyo University, a Francophile and Francophone, a critic and theoretician who, like his young contemporary at the time, Asada Akira, introduced the works of Roland Barthes, Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida to Japanese academia. He was also invited to conceive programmes for genre filmmakers such as Suzuki Seijun and Tai Kato at prestigious international festivals. Lastly, he became president of the prestigious University of Tokyo. Serge Daney‘s magazine Trafic published a number of his essays, notably on John Ford ; among his admirers in France are Jean-Michel Frodon, formerly director of Cahiers du Cinéma and critic for Le Monde, and Mathieu Capel translator and specialist of Yoshida Kiju‘s work.

But at a time when French reflection on Ozu Yasujiro takes the form of a coffee table book by Pascal Alex Vincent (1), the Hasumi method, inevitably quoted, has attracted in France a limited number of university researchers. As for the perception of Ozu‘s work within French cinephilia, it is fair to say that it has taken precedence over that of his peers.

The Anglo-Saxon university scene is quite different, and the number of professors and doctoral students examining Hasumi is surprising in its enthusiasm and in the proximity between members of this community. In such a context, the work accomplished by Ryan Cook should earn him their praise. But for those who want to discover Hasumi‘s vision of Ozu, or rediscover it, this translation is now a masterly reference tool. Cook, himself a film professor who devoted himself to this task, has a mastery of Japanese language and writing. In his introduction he insists on the latter and on his desire to emphasize what Hasumi did with it, recalling Barthes’ effect of a degree zero, as well as the author’s literary studies and the probable influence of Flaubert on his writing.

Ryan Cook also announces his determination to translate Hasumi‘s style, evoking the exact title of the work, meaning ‘directed by Yasujiro Ozu’, and dreaming of its translation ‘directed by Shiguéhiko Hasumi’.

However, Hasumi was in charge of the French version, joined by two major translators of Japanese literature, and in this respect the two versions are significantly different. The reader of this new translation will be more likely to haunt the spheres of academia.

At the start of his introductory essay, Aaron Gerow turns to the film magazine, Sight & Sound, and the rankings for Tokyo Story and Late Spring in their list of the one hundred best films. He correctly raises important points, not least the power Hasumi wielded over a generation of students who would go on to become critics and filmmakers (2), gathering around the Japanese edition of Cahiers du Cinéma. Even today, Hamaguchi Ryusuke (Murakami Haruki‘s adaptor) insists that this book was the most important of his life (calling for caution on the part of the reader…). But also that there are now new international researchers who can read the texts in the language, and contribute essays in Japanese, in the manner of those who made the opposite journey, such as Kinoshita Chika. This point touches on one of Hasumi‘s operative criticisms, as he offers little praise for Paul Schrader‘s book, or David Bordwell‘s, or any of the others that persist in making Ozu a filmmaker of the minimal, whereas what is Ozuesque for Hasumi lies in figures of abundance.

There are chapters listing the actions, states and delicacies that the characters undergo, go through and prepare, before reaching emotion. Gerow reminds us that Hasumi is less concerned with an auteurist celebration of Ozu than with an opportunity to criticise the very notion of the auteur, to the point of ‘sacrificing this auteurist unity’ (3). In 1983, the notion of auteur was a fragile commodity within French theory…

For those of us who don’t read kanji, who might struggle to find our way through Hasumi‘s sentences, whose length rivals Proust or Henry James, this meticulous and precise version, in direct contact with the text, with a maverick edge, will be a landmark.

Stephen Sarrazin.

1- The same publisher, Carlotta, also published Ozu’s notebooks. PA Vincent does it again in a recent box set of unreleased Ozu films, begging the question as to who else will speak for the filmmaker in France.

2- These include Aoyama Shinji, Shinozaki Makoto, with sempai Kurosawa Kiyoshi. We should also remember that in 1999, a year after the French publication of his Ozu, Hasumi spoke to Kitano Takeshi for his episode of Cinéma de notre Temps.

3- Aaron Gerow, Hasumi Shigehiko and Viewing Films Studies Anew, in Directed by Yasujiro Ozu.

Follow

Follow